Security Alert: Scam Text Messages

We’re aware that some nabtrade clients have received text messages claiming to be from [nabtrade securities], asking them to click a link to remove restrictions on their nabtrade account. Please be aware this is likely a scam. Do not click on any links in these messages. nabtrade will never ask you to click on a link via a text message to verify or unlock your account.

In debt we (can no longer) trust

Andrew Canobi | Franklin Templeton

The US is close to hitting its congressionally mandated debt limit. This event comes about every few years because the US government has a legislated dollar cap on the borrowing authority of the treasury which can only be increased by an act of Congress. The Treasury has recently suggested it could run out of money as soon as early June.

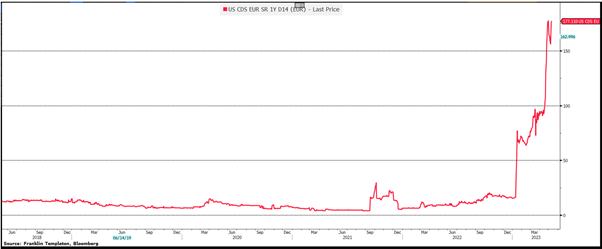

One-year sovereign credit default swaps on the US are trading at ~177bps. The long run average is ~15bps.

US 1-Year CDS Price

Source: Livewire Markets 2023

If you go long US sovereign CDS for a year in the amount of, say $10m, and the US defaults, your counterparty will deliver you $10m of treasury bills and you will pay them $10m. You can then march off to Janet Yellen’s office (US Secretary of the Treasury) and ask for your money back.

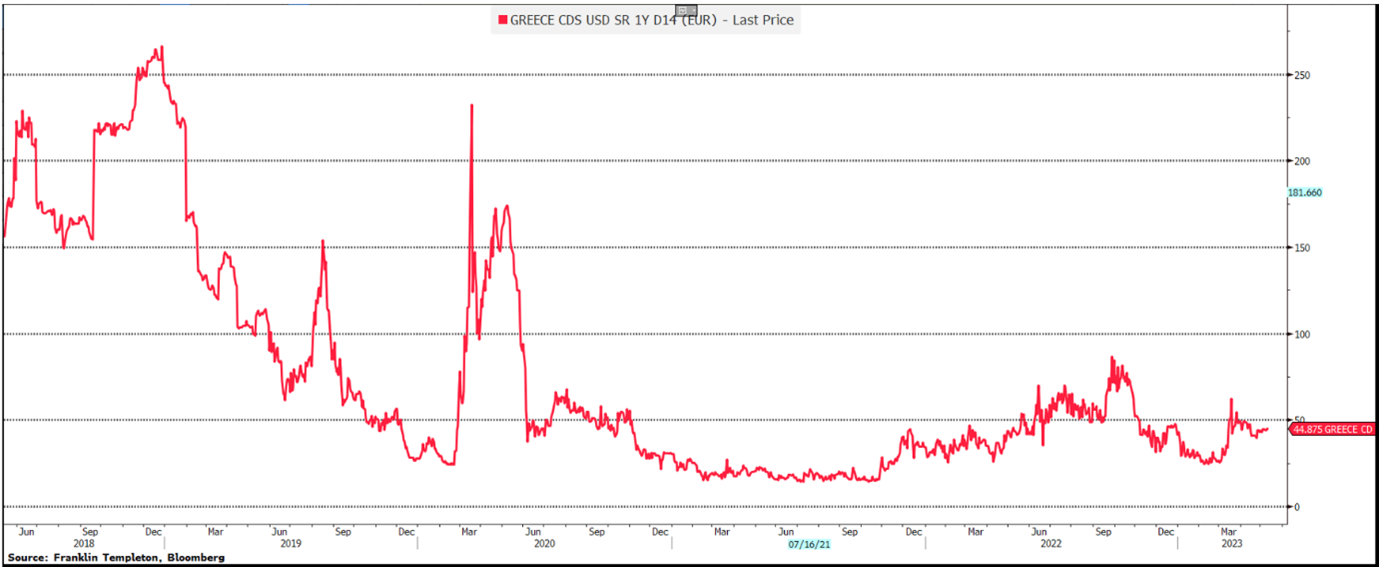

To add insult to injury, Greek CDS for 1-year is currently trading at 45bps. We can’t even believe we are writing this.

Greece 1-Year CDS Price

Source: Livewire Markets 2023

When excessive debt is accumulated over time, it is deflationary. This is because debt enables growth to be purchased from the future and brought forward to the present. In the short-term, growth benefits from excess demand. Once the sugar rush fades, the liabilities remain and weigh on demand as the piper has to be paid. The pandemic saw a surge in borrowing which financed stimulus programs from JobKeeper in Australia to the Payroll Protection Plan in the US. The bigger picture playing out across the world is one of the fiscal chickens now coming home to roost. Governments are now focussed on the task of not adding to inflationary pressures and recovering from the debt fuelled spending of the pandemic. This is a delicate task.

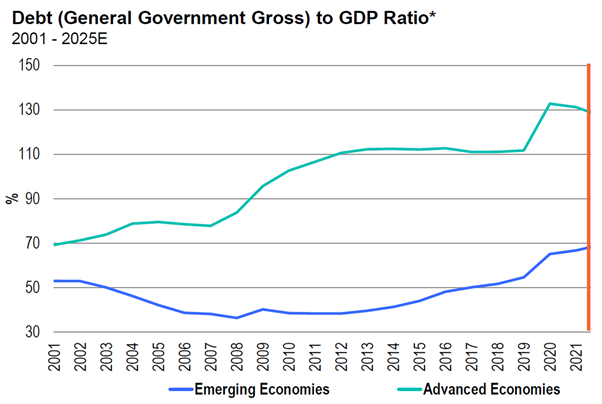

The chart below illustrates that the sluice gates were opened across developed economies via fiscal measures during the pandemic. This step change in government demand was fuelled by large amounts of borrowing and is now over. Like Australia, few countries can expect to produce a surplus anytime soon, but the huge spending programs experienced in COVID are now necessarily giving way to restraint.

*Source: Franklin Templeton; Macrobond

Research from the Australian National University has recently argued what is intuitive – the majority (around 4/5) of the current inflation challenge was the result of excess government stimulus and only a minority (around 1/5) is due to easy monetary policy. This should surprise no-one if we consider that in the course of the pandemic, government (State and Federal) essentially borrowed greater than ~A$400bn and poured it into the economy with much of it hitting bank accounts in short order. As well intentioned as that may have been in the moment, we now know that this was inflationary. To be fair, unemployment at record lows of 3.5%, with wages growing at a decent clip is also an outcome of this stimulus. It isn’t all negative by any stretch.

Australia does not have a legislated debt limit like the US and has just passed its first full year budget under the new Labor government. But fiscal policy can no longer be the source of huge stimulus it was in the pandemic. Whether or not the Australian budget adds or is neutral for inflation, it necessarily is a far cry from the role it played in 2020-22. We may not be in an era of austerity, but we are necessarily in an era of constraint.

The chart below from the Federal budget papers highlights what fiscal stimulus looks like. It also highlights that we now are only slowly mapping a path back toward balance/surplus as deficits are still forecast for the coming years to average 1-1.5% of GDP. The excess money from the blue spike upward is now being largely left to the RBA to mop up. We think this process is being effective (perhaps overly so) as evidenced by data showing Q1, 2023 retail sales volumes fell by the largest percentage since 2009, excluding the COVID lockdown period.

We don’t expect the US to default because the debt ceiling isn’t raised. Like many previous negotiations it will be messy and potentially an 11th hour event, but the base case is some sort of agreement to increase the limit. The risk of the alternate case is low however, and risks are arguably higher than in previous episodes. That won’t alter the challenge facing the US over the next 10 years where the Congressional Budget Office forecasts deficits averaging more than 5% of GDP every year. They also forecast gross government debt goes from the current ~US$32trillion to $52trillion.

For the history buffs, Australia did have a debt limit between 2007 and 2013 introduced by the then Labor Government under Kevin Rudd and set at $75bn. It was increased to $200bn in 2009, $250bn in 2011, $300bn in 2013 and junked altogether later in 2013 by the then Liberal Government under Tony Abbott.

This team is old enough to remember the feedback discussions held by then treasurer Peter Costello on the merits of completely paying off Commonwealth Government debt in the years preceding the GFC. Those days are ancient history now.

Learn how the industry leaders are navigating today's market every morning at 6am. Access Livewire Markets Today.

Andrew Canobi is director of Australia Fixed Income for Franklin Templeton Australia. All prices and analysis at 23 May 2023. This information was produced by Andrew Canobi and published by Livewire Markets (ABN 24 112 294 649), which is an Australian Financial Services Licensee (Licence No. 286 531).This material is intended to provide general advice only. It has been prepared without having regard to or taking into account any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation and/or needs. All investors should therefore consider the appropriateness of the advice, in light of their own objectives, financial situation and/or needs, before acting on the advice. This article does not reflect the views of WealthHub Securities Limited.