Security Alert: Scam Text Messages

We’re aware that some nabtrade clients have received text messages claiming to be from [nabtrade securities], asking them to click a link to remove restrictions on their nabtrade account. Please be aware this is likely a scam. Do not click on any links in these messages. nabtrade will never ask you to click on a link via a text message to verify or unlock your account.

Bigger fall, bigger bounce: small caps into and out of recessions

All types of investing require nerve and courage, but perhaps none more so than small-cap stocks. When an economic downturn hits, small caps tend to fall first and farthest.

That has been the case in the current down market and US small caps have slumped 30% from November 2021 highs. Outside of the COVID drawdown, that’s the worst fall for US small caps in a 10-month or less period in the last 70 years.

But while small caps fall the hardest, they also recover the fastest.

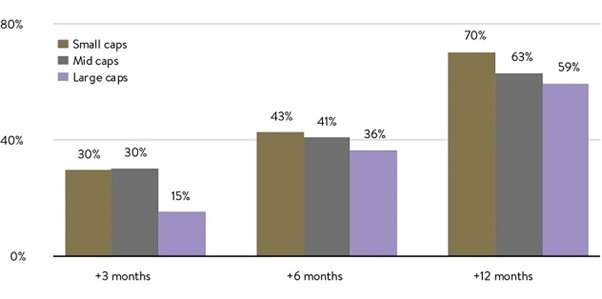

Historically, in the 12 months after the US small-cap index has bottomed around a recession, they have returned an incredible 70% on average, or 11% higher than large caps (see chart below). The small-cap rebound is also quick: most of the additional return benefit versus large caps has happened in the first three months.

Small caps have the edge over mid and large after trough

Source: BofA ETF research, Ibbotson, Global Financial Data.

If investors can understand the dynamics behind small-cap volatility, they will less likely be whipsawed out of small-cap stocks, but also be more confident in positioning their portfolios for a strong rally.

Why smalls tend to fall more

There are many reasons why the small-cap sector falls hard. They are generally not traded as heavily, so when institutional investors become nervous, they will often sell at the smaller end of the market because they fear they will become trapped in these less liquid positions.

When these big institutions turn bearish, the impact on small caps can be significant, creating something of a vicious cycle: small-cap managers begin to believe that they, too, must preserve cash. They then also stop buying, pushing prices down further and faster on even lower levels of liquidity. And while small-cap managers might see even cheaper stocks, many are unwilling to enter the market so prices in small-cap stocks keep falling at a faster rate

Small-cap companies also tend to be more sensitive to changes in the economy. They are less able to diversify their operations and are less likely to have the large cash reserves needed to withstand difficult trading conditions. That means that there is a higher chance of them going bankrupt.

Depths of despair

But just when things look hopeless for small caps, the point of recovery comes like a tsunami, often bringing with it stellar returns.

As any good surfer knows, it’s important to be positioned early – in this case for when the big institutions once again look for investments in small caps that produce returns above the market average.

No one knows the timing of all this. But one sign is that, when everyone thinks investors are crazy for going into small caps, that is the very time when it is a great idea to invest in them. It means it is not just necessary to have nerve, investors must be willing to follow their own judgement, even if it means going against the herd or ‘expert’ opinion.

Positioning to surf the recovery wave

So where are we in this cycle? We make three observations:

1. Poor news is priced into small caps

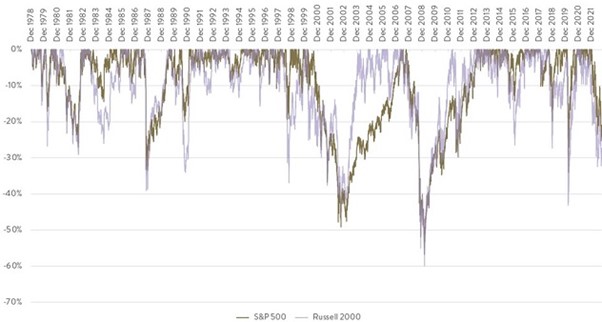

Firstly, there seems to be a lot of bad news already factored into small caps. The Russell 2000’s recent 30% drop from highs (versus a 36% drop on average around recessions since 1950) suggests that small-cap equities may be pricing in more recession risk than large caps, which have fallen a more modest 23% (S&P 500).

US Equities Drawdown

Source: Factset

2. Large caps may not be more resilient this time around

Large caps may not retain their resilience over small caps during this downturn. In previous downturns, large-cap stocks were seen by the market as being more resilient because they were more likely to have globalised operations and consumer bases. (In 2008 the strength of China’s economy helped global companies survive the extreme stresses.)

That is less likely to happen this time around. The economic downturn is global, sparked by higher inflation, and in the wake of the pandemic there has been significant fragmentation of international supply chains. The ability to disaggregate production across different geographical regions, which has been a distinct advantage many large caps enjoyed over smaller companies, may prove to be more of a disadvantage this time.

3. Small caps are cheap

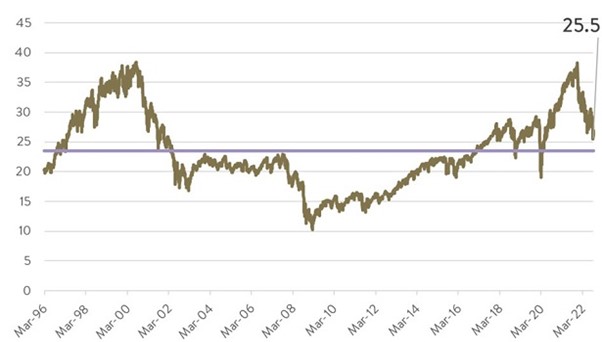

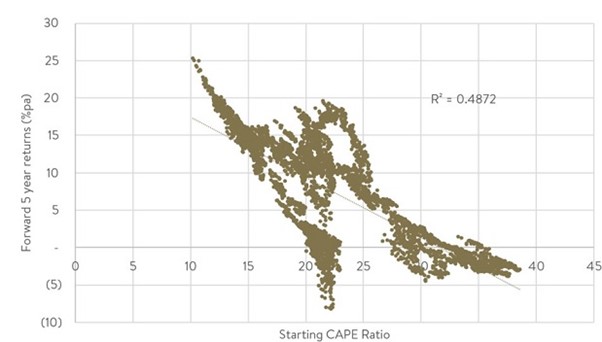

And, thirdly, US small caps look cheap. The Russell 2000 is currently trading at a 17.3x long-term price-earnings (PE) ratio. When the Russell 2000 has been at that value historically investors have benefited from double-digit average annualised returns over the next 5 years. The Russell 2000’s valuation is also over 30% cheaper than the 25.5x long-term PE ratio for the S&P 500, which has historically resulted in average annualised returns over the next five years in the low single digits.

Russell 2000 CAPE Ratio

Source: Factset.

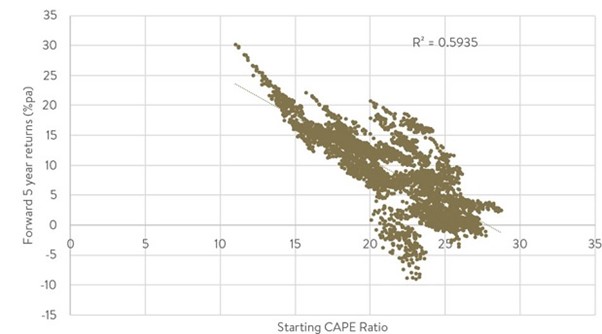

Starting Russell 2000 CAPE Ratio and subsequent 5 Year Returns

Source: Factset.

S&P 500 CAPE Ratio

Starting S&P 500 CAPE Ratio and subsequent 5 Year Returns

Source: Factset.

Strong returns potential

We may not yet have the catalyst for a sustained rebound in share markets given the source of its falls – high inflation – has not been fully dealt with yet. But we see more limited downside for small caps given what has already been priced in. Indeed, we see strong absolute returns ahead over the next few years once the recovery takes hold, given starting valuations and likely attractive relative returns to more expensive large caps.

There may be further declines to come, but the risk of weakness in the small-cap sector is outweighed by the risk of missing out on the eventual strong recovery that history suggests is likely to occur.

We remain acutely aware of this coming opportunity and have a game plan in place to ensure we can take advantage of it. We encourage other investors to do the same.

First published on the Firstlinks Newsletter. A free subscription for nabtrade clients is available here.

Andrew Mitchell is Director and Senior Portfolio Manager at Ophir Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. Analysis as at 19 October 2022. This information has been provided by Firstlinks, a publication of Morningstar Australasia (ABN: 95 090 665 544, AFSL 240892), for WealthHub Securities Ltd ABN 83 089 718 249 AFSL No. 230704 (WealthHub Securities, we), a Market Participant under the ASIC Market Integrity Rules and a wholly owned subsidiary of National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937 AFSL 230686 (NAB). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken by WealthHub Securities in reviewing this material, this content does not represent the view or opinions of WealthHub Securities. Any statements as to past performance do not represent future performance. Any advice contained in the Information has been prepared by WealthHub Securities without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any such advice, we recommend that you consider whether it is appropriate for your circumstances.