Security Alert: Scam Text Messages

We’re aware that some nabtrade clients have received text messages claiming to be from [nabtrade securities], asking them to click a link to remove restrictions on their nabtrade account. Please be aware this is likely a scam. Do not click on any links in these messages. nabtrade will never ask you to click on a link via a text message to verify or unlock your account.

Is it all falling apart for central banks?

Years of rapid financialisation has led to colossal debt growth with low interest rates and quantitative easing (QE) helping to push asset prices higher. The tide is rapidly reversing, at least for now. Central banks are unable to ignore inflation, but both inflation and employment are lagging indicators.

We are now working through the consequences of the excessive fiscal and monetary stimulus delivered 18 months ago in the pandemic. A good example of the scale of that excess is real disposable income rising more than 15% in the US over the 2020/2021 period despite the economy being in recession as a deluge of fiscal transfer payments overwhelmed the actual loss of salaries and wages.

As well-intentioned as fiscal policy was, with the benefit of hindsight, it clearly exceeded requirements across the world. Global Debt/GDP is at record levels and markets have unquestionably been fuelled by an extended era of ultra-easy money. Unfortunately, the probability of this ending well is extremely low as the monetary action being taken right now will manifest itself in significantly weaker growth over the coming twelve months.

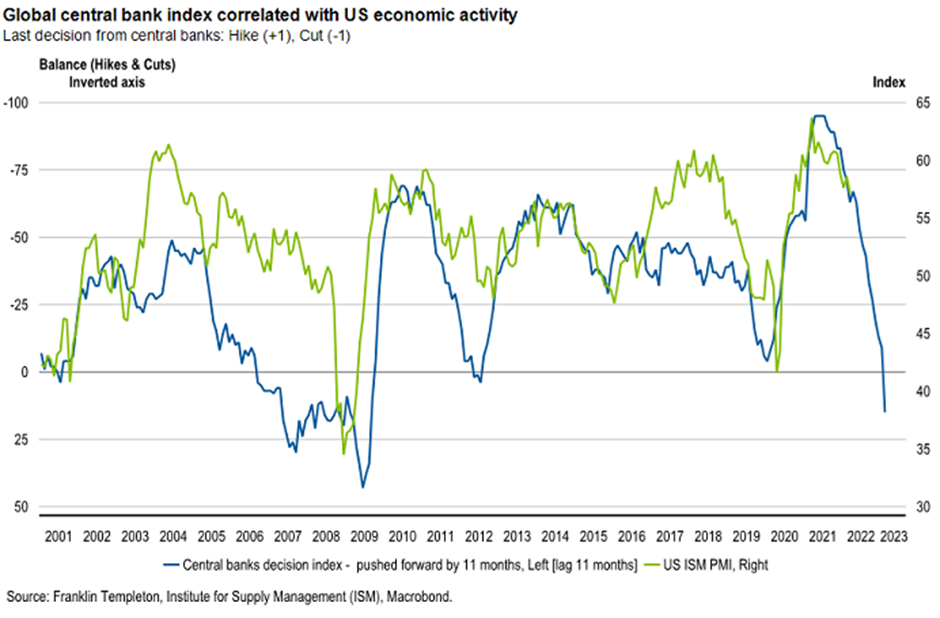

The chart below shows that across 125 central banks, we have seen a monetary tightening campaign to take conditions into the most restrictive since the GFC (blue line inverted). This is before moves this week, particularly from the Fed which likely moves by 50bps.

Advancing this index by 11 months against the US manufacturing ISM PMI shows how this story will end. Recession and early signs are already confirming that downturn. Just as inflation is a lagging indicator so changes in monetary policy work with lags which will show up over coming months and quarters.

The difficulty is central banks must respond to the here and now even as lags prevail. Last week’s first quarter Australian CPI cannot be dismissed easily. 5.1% annual headline CPI is the fastest in more than 20 years and the measure showed some ~88 items in the ABS’ basket recorded price gains. It’s not the end of the world and its certainly not the 1970s. In many respects, everything that could have conspired to push prices higher in Q1 did. But there are some slivers of hope to consider:

1. Housing

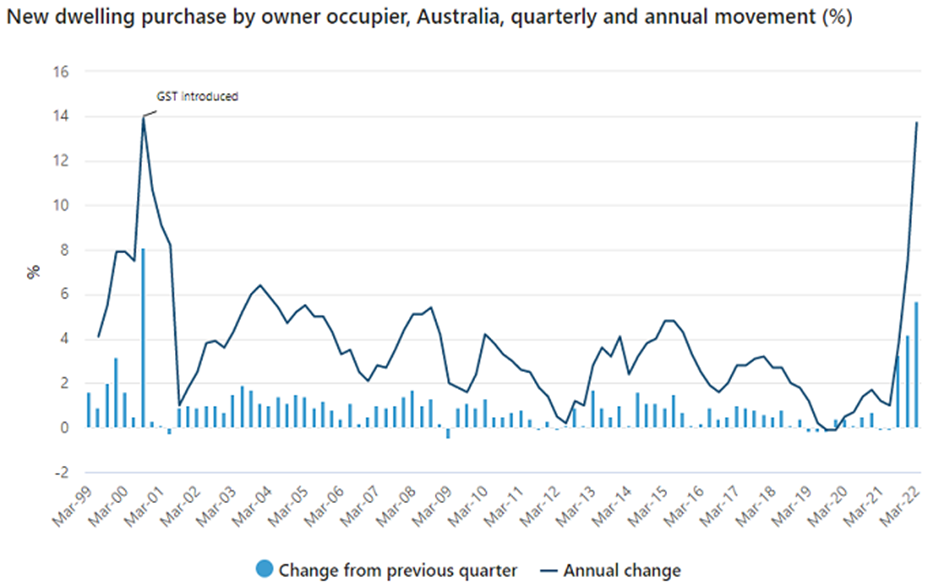

Housing has been one of the strongest sources of inflation pressure in the last 12 months. We are now experiencing the consequence of over stimulating housing at a time when supply of construction materials and labour was materially constrained. Construction costs for building a new home was one of the larger components that exceeded forecasts contributing 0.62% of the 2.1% quarterly number alone.

Source: Australia Bureau of Statistics

There are many reasons to suggest that we are moving past peak housing mania but it will take time to show up. Higher costs, the winding down of homebuilders, higher interest rates (which have already been moving as banks raise rates on fixed rate products in particular) and just the natural normalisation of housing demand will all cool construction.

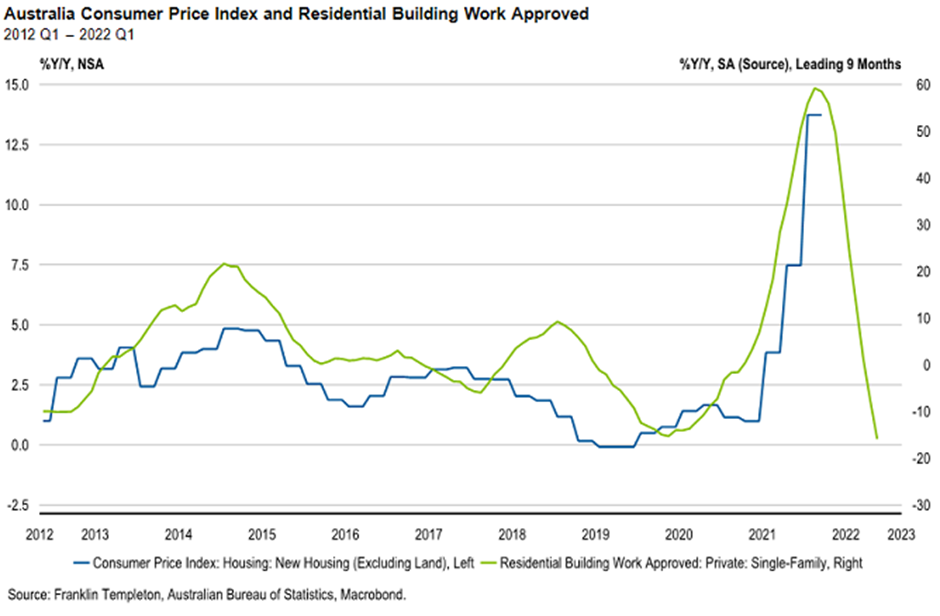

The chart below highlights the relationship between residential building approvals which exploded in 2020/21 (but is now in the rear-view mirror) and construction costs. In short, the worst might be past. We pay particular attention to the housing market because, as per the saying, as goes the housing market so goes the economy. Even the hint of higher interest rates is clearly starting to add to the list of headwinds for the sector with auction clearance rates already at multi year lows and Sydney house prices now down for two consecutive months (Corelogic data).

2. Non-discretionary prices

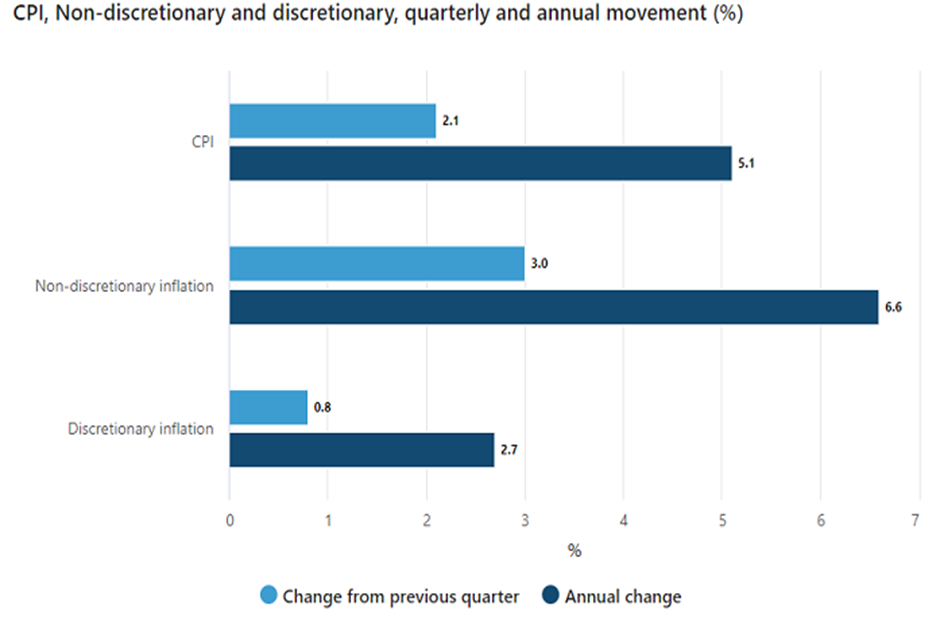

The RBA, along with other central banks, will be mindful of the moves in areas like food and energy and key non-discretionary prices. Increases in these areas act as de facto tightening as households can’t choose to not eat or fill up the car. That is why core inflation ex these items is the focus for them. Core inflation of 3.7% is a concern but it’s not seismically above the 3.25% in their 2022 forecasts. The ABS points out that non-discretionary CPI grew at more than twice the pace of discretionary.

In some ways, in Q1 everything that could go wrong, did. From the Ukraine conflict impacting energy prices to floods in NSW and QLD adding to food inflation. Which doesn’t mean the RBA won’t respond but it highlights that prices of non-discretionary items are already doing some of the work for them in curbing demand. The risk when price pressures spread is a more broad-based cycle leading into a wage-price spiral. So doing nothing is not an option.

Source: Australia Bureau of Statistics

Source: Australia Bureau of Statistics

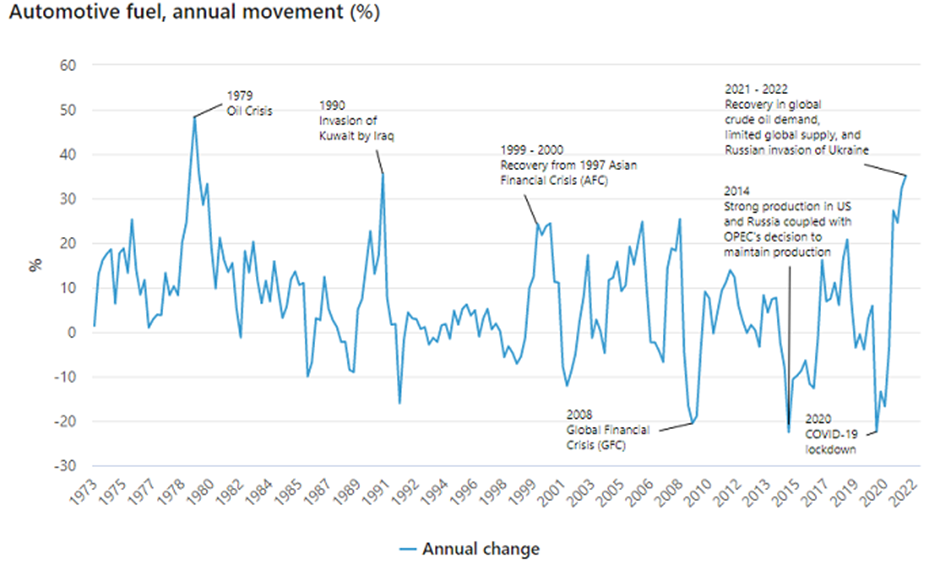

Within this category, energy prices faced a perfect storm in Q1. Prices may stay elevated for some time but a 30% plus move from here is clearly much less likely.

Source: Australia Bureau of Statistics

3. Inflation

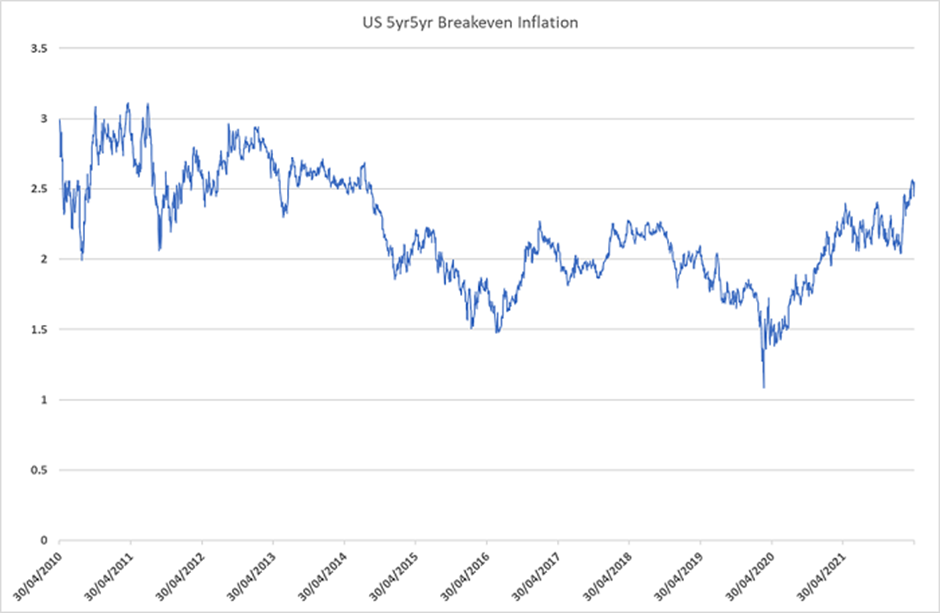

Markets continue to believe inflation is not likely to be a persistent phenomenon and that central banks are going to be effective in dealing with it. The US led the developed world in this inflationary cycle and we continue to look to at the US economy for signs of a peak. Longer term expectations for inflation remain well anchored. It is striking that despite a ~8.5% headline inflation level in the US (as at the most recent print) the closely watched US 5yr5yr forward breakeven rate remains only a little above recent averages at ~2.54%.

Source: Franklin Templeton, Bloomberg

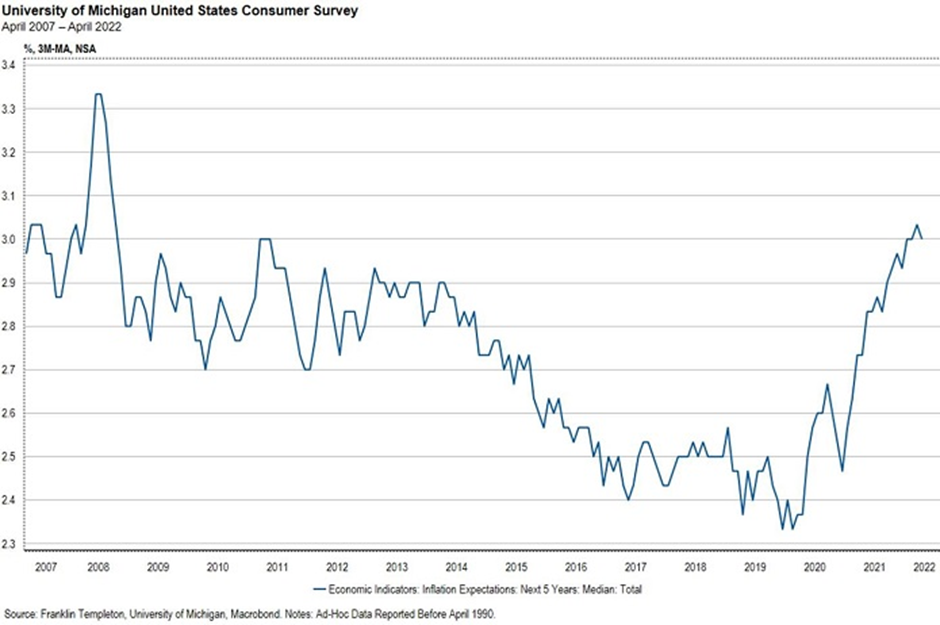

Survey based measures of inflation expectations also remain anchored albeit higher than their previous low levels. The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment survey of longer-term inflation expectations has risen but is still at levels around 2012/13. Policy makers don’t want to see these rise much further but if a peak is close that risk should be limited.

The risks are that the longer headline inflation persists the greater the risk that longer term measures of expectations become ‘unanchored’ leading to a wage-price spiral. We are not there yet and markets do expect it. There is no disagreement that US inflation will slow from its current lofty heights. There is disagreement about the pace and extent, but the signalling this will convey will be powerful for the world. This will be an important and powerful signpost that we are passing a peak in the developed world which will be important for Australian dynamics where an unhelpful assumption has been made that so the US goes, so goes Australia.

4. Monetary policy

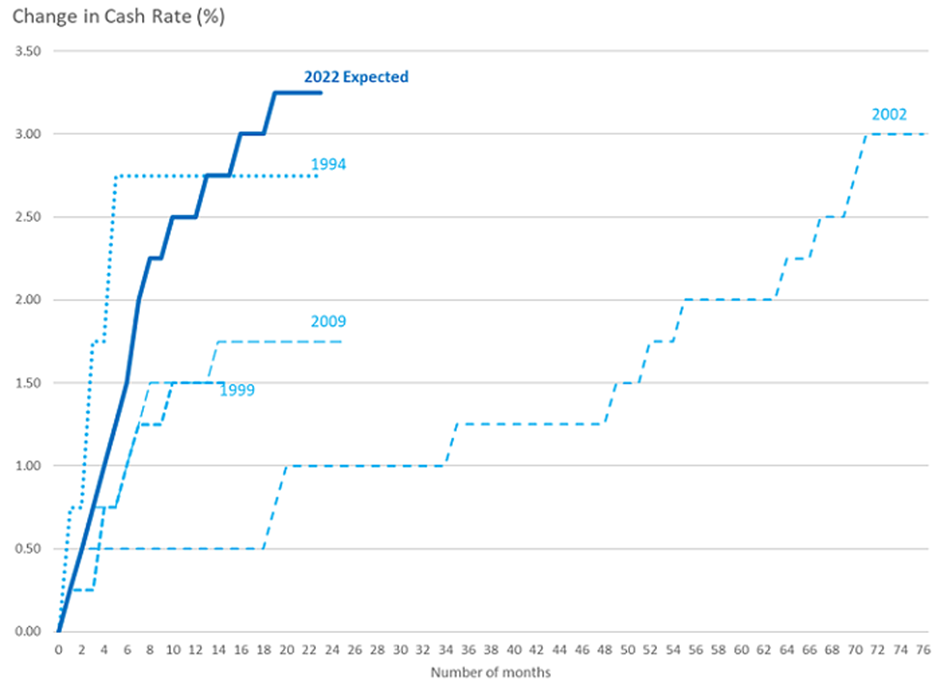

Monetary policy will still not be anywhere near as aggressive as markets expect. Below we show what is implied by current market pricing for the RBA versus the last 4 rate hike cycles going all the way back to 1990. In short, markets continue to project the most aggressive tightening cycle to ensue in more than 30 years. Both in terms of speed of move and size of rate hikes themselves.

With household debt levels at record highs and consumer confidence already weak, a cash rate as implied by current markets would likely push Australia into a housing led recession. What the RBA actually delivers and where the cash rate ends up is the most significant driver for bond market returns over the next year.

Our view hasn’t changed that the RBA will take a measured approach to raise rates and likely end up with a terminal rate in the 1.25% area. It could be slightly higher, but it is almost certainly not going to be the 3.5% now priced by markets.

Source: Franklin Templeton, Bloomberg

These are perilous times with markets already feeling the chill of the monetary deep freeze underway - the Nasdaq is down more than 20% YTD, emerging market currencies have fallen significantly and real estate markets are showing signs of weakness. The probability of central banks gently landing the plane looks to be shrinking by the day. Global financialisation is facing its biggest hurdle since the GFC.

First published on the Firstlinks Newsletter. A free subscription for nabtrade clients is available here.

Andrew Canobi is a Director, Fixed Income; Joshua Rout, CFA, is a Portfolio Manager and Research Analyst, Fixed Income; and Chris Siniakov is Managing Director, Fixed Income at Franklin Templeton, a sponsor of Firstlinks. Analysis as at 11 May 2022. This information has been provided by Firstlinks, a publication of Morningstar Australasia (ABN: 95 090 665 544, AFSL 240892), for WealthHub Securities Ltd ABN 83 089 718 249 AFSL No. 230704 (WealthHub Securities, we), a Market Participant under the ASIC Market Integrity Rules and a wholly owned subsidiary of National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937 AFSL 230686 (NAB). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken by WealthHub Securities in reviewing this material, this content does not represent the view or opinions of WealthHub Securities. Any statements as to past performance do not represent future performance. Any advice contained in the Information has been prepared by WealthHub Securities without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any such advice, we recommend that you consider whether it is appropriate for your circumstances.