Security Alert: Scam Text Messages

We’re aware that some nabtrade clients have received text messages claiming to be from [nabtrade securities], asking them to click a link to remove restrictions on their nabtrade account. Please be aware this is likely a scam. Do not click on any links in these messages. nabtrade will never ask you to click on a link via a text message to verify or unlock your account.

Why you shouldn’t access your super early

A political and policy stoush is playing out between Senator Jane Hume and former Prime Minister, Paul Keating, over the merit of allowing people to access their superannuation early in response to COVID-19. Jane Hume is Assistant Minister for Superannuation, Financial Services and Financial Technology, and leads the Government’s prosecution on super policy. Paul Keating is widely considered the father our of super system and he does not like upstarts tinkering with his rules.

The scoreboard on early access to super

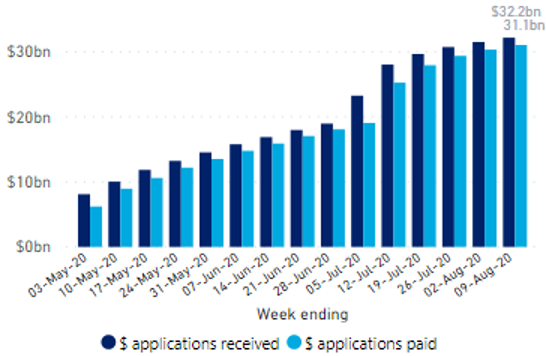

Treasury initially estimated that $29 billion would be withdrawn from super when the early release was announced in response to COVID-19. With the scheme now extended until the end of 2020, the estimate has been revised to $42 billion. Around 2.6 million people have used the scheme, with an estimated 620,000 emptying their super accounts completely. Here is progress to 9 August 2020 according to APRA, reaching $32 billion with the average payment of $7,700 and 97% of applications approved.

Value of applications (cumulative)

What is Hume versus Keating about?

In response to the pandemic, contradicting the previous firm policy to lock up super until retirement, the Government and Hume are prosecuting the view on super that “it’s your money”. That is, people are entitled to access it early if they need to. Consider this interview with Laura Jayes on Sky News on 21 April 2020.

Jayes: Is there a chance here that if we do see a lot of young people take up this offer of essentially $20,000 of early money from their superannuation, does it weaken the system years down the track and is that just putting off a problem for another day?

Hume: Well, we think people are best placed to make those decisions themselves and you've got to think about the counterfactual. What would be the effect of leaving that money in superannuation but not being able to pay your mortgage, not being able to pay off a credit card, having to sell something like your car just to get by? So it really is a decision for individuals. We're certainly not encouraging people to take up the offer but we're giving them the option to make an assessment about their own financial situation, their own family budgets.

So the money belongs to the investor and if they need it for “their own financial situation, their own family budgets”, they are entitled to have it. “It’s your money” she also said.

Keating calls this "generational theft". He spoke at a virtual conference run by Industry Super Australia on 4 August 2020:

“It is a breach of the preservation rules to just let anyone take out their money willy-nilly. There has been no scrutiny whatsoever ... The whole point of superannuation was a great public bargain with the community: defer consumption for your working life and you will get a very low rate of tax.”

Keating argued that much of the money was probably spent on discretionary items such as cars, boats and motorcycles, and the long-term savings of young Australians are now compromised. As others have argued, the people who needed money could have been protected by the right fiscal policy:

“Every dollar which came out of young peoples' super balances could have been funded by one press of the computer button at the Reserve Bank.”

Is access too easy?

Qualifying for early release requires a loss of job or reduction in working hours of at least 20% since 1 January 2020. While this sounds like a high bar, the lax part was not so much these tests but the simple online application process with no vetting.

The ATO confirmed the online access was easy. Second Commissioner Jeremy Hirschhorn told a Senate committee that the ATO did not check eligibility due to the dire circumstances around the pandemic:

"This is about getting emergency money to people. We will never have enough information to reject quickly, we will give people their money on the basis of their say so.”

So the ATO assumed people were honest. Brave. The Government does not trust people for anything relating to social security, where pensioners are subject to close scrutiny and checks. After the initial flurry, the Government issued warnings about compliance and penalties, but it did little to halt applications. Hume continued to defend the system and the applicants, saying:

“Australians who have made the decision to access their super early can rest assured that the Morrison government trusts them. They understand that withdrawing some money now comes with a trade-off down the track—but the decision is theirs.”

This is a long way from the previous tightly-controlled compassionate access.

Whatever happened to super’s objective?

Remember the good old days - if 2015 can be called old - when most people supported the objective of superannuation. David Murray’s Financial System Inquiry had recommended that:

“the objective of the superannuation system is to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the age pension.”

In October 2015, the Liberal Government announced it would enshrine the objective in legislation, it issued a discussion paper in March 2016 and by November 2016, the Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016, was introduced. Then it stalled, and we are now further away from defining the objective than five years ago.

And let’s not forget the sole purpose test

To quote directly from the ATO website’s SMSF section on the sole purpose test:

“Your SMSF needs to meet the sole purpose test to be eligible for the tax concessions normally available to super funds. This means your fund needs to be maintained for the sole purpose of providing retirement benefits to your members, or to their dependants if a member dies before retirement.

Contravening the sole purpose test is very serious. In addition to the fund losing its concessional tax treatment, trustees could face civil and criminal penalties.”

That’s unambiguous. The fund is maintained to provide retirement benefits.

What was the money spent on?

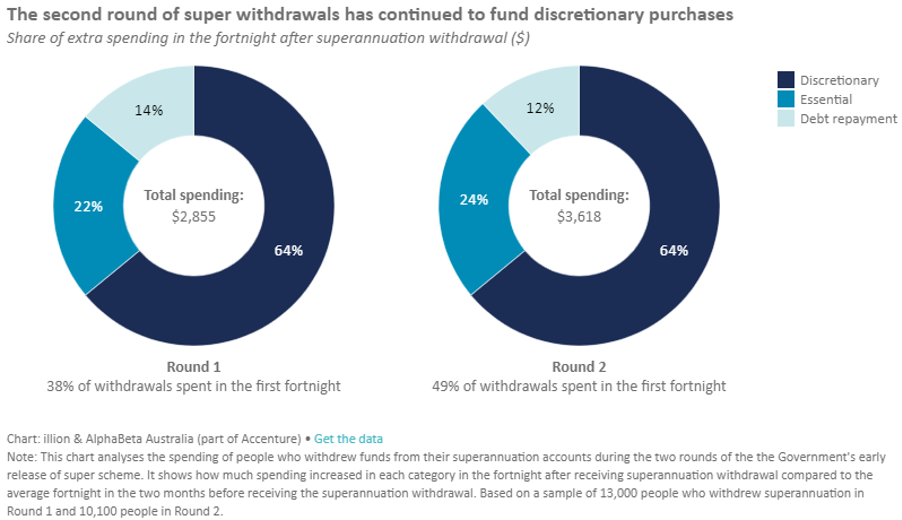

The most frequently quoted data tracking the use of early super withdrawals comes from consulting firm AlphaBeta (part of Accenture) and credit bureau, illion. They claim that 40% of people who accessed super early had experienced no fall in their income during the COVID-19 crisis, and only 22% in Round 1 and 24% in Round 2 of withdrawals were spent on essentials. Discretionary items included gambling (11% of money spent) and clothing (10%), while 12% in Round 2 was for debt repayment, as shown below. Hume has disputed these results.

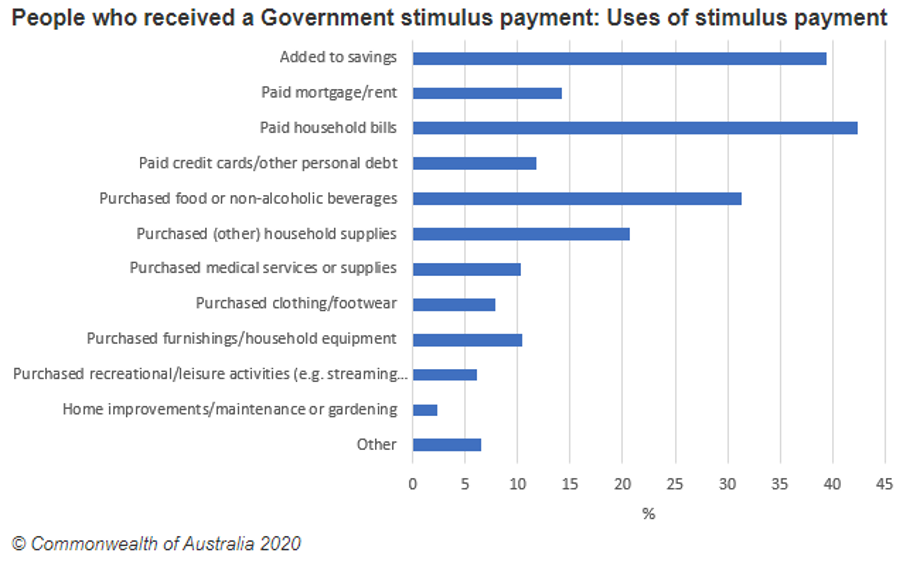

The ABS has produced separate data on the way stimulus payments such as JobKeeper have been used.

Notwithstanding the lack of firm evidence, no doubt much of the money directed at retailers such as Kogan and JB Hi Fi, who have experienced rapid increases in sales in recent months, came from both stimulus spending and people accessing their super.

Implications of the early withdrawals

What are the consequences of this early access? Here are two:

1. Decline in total super in the system in future

Early access to super will compound the adverse impact of COVID-19 on future super balances, with BetaShares estimating the $30 billion withdrawn to date will reduce future balances by over $100 billion:

“An amount between $100 billion and $130 billion represents a very significant future shortfall (which will only increase as further super is released early). It will need to be funded by future Australian governments and therefore the Australian public will ultimately bear the cost, as those who have withdrawn super will be less able to fully fund their own retirement needs.”

Other estimates place this in a broader context of future super reductions due to COVID-19. Current superannuation balances are about $3 trillion, and Rainmaker previously projected retirement savings would reach $10 trillion over the next two decades. Their Superannuation Projection Model has now revised the number to $7 trillion due to the virus, including the impacts of rising unemployment, lower super contributions, lower long-run earnings and reduced population growth.

2. Lower personal superannuation balances

Assuming savings grow annually at a rate of 3% above inflation less 0.5% administration fees, the withdrawal of $20,000 has a different impact depending on age. A younger person at 30 loses $50,000 in their retirement balance.

Current age | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 |

Loss of retirement balance | $50,000 | $39,000 | $30,000 | $24,000 |

The estimates obviously depend on the assumptions and it's easy to derive bigger numbers. For example, BetaShares reports:

"Based on an annual growth rate of 5% plus CPI, $10,000 withdrawn today becomes a $70,400 nest egg over 40 years. When an average annual rate of 7% plus CPI is used, this increases to $149,745."

Either way, the predominantly young people withdrawing their super will miss out on compounding over so many years that their super balances will face a big hit.

'It's your money' versus lockup

Anyone sitting in the ivory tower of a well-paid job and a paid-off mortgage during the pandemic should not judge the struggler who withdraws their super to pay the rent, feed the family or fix the car. There is also a case to access super early for productive reasons such as buying a home, a crucial step on the ladder to financial independence and security in retirement.

However, where the money is used for short-term wants rather than needs, people who spend their super are doing themselves a disservice. Even if in future they are likely to qualify for the age pension, they should supplement reliance on government support with other assets. Nobody knows how generous or otherwise the age pension will be 20 or 30 years from now. Buying a big-screen television or fancy new car as a lifestyle decision instead of allowing compounding to build savings for retirement may have long-term adverse consequences.

Compulsion and tax advantages are usually necessary to make people save for retirement, and Australia has a system recognised as a role model around the world. It included highly-restricted access before retirement, and there will be other crises in coming years where super might be opened again.

Ideally, the Government could have recognised the genuinely needy during the pandemic and set up another scheme to assist them without invading their super. "It's your money" flies in the face of the strict access rules we have accepted since 1992, and many are compromising their future in exchange for current consumption.