Collateral damage follows the end of profitless prosperity

The end of the free money epoch is now well and truly upon us. Over the last six months, the US Federal Reserve has pivoted from telling markets interest rates would remain at zero during 2022 to warning them it would move ‘expeditiously’ to a neutral setting. Meanwhile, supply chain disruptions and a lack of labour have contributed to previously unfathomable price increases for finished goods and services. And finally, Covid in China and a war in Ukraine have resulted in rapid increases in raw materials, fuel, and food.

Free money has its consequences

The free money experiment is at an end, absent a desperate act by central banks to kick the can down the road again, ahead of a yet unlikely deep recession.

There will many consequences of the end of free money including the impact of the misallocation of capital by venture capital and private equity during the free money bonanza.

We will eventually look back on this period as one defined by 'profitless prosperity'. This era permitted companies with no profit, and no prospect of making any, to exist. All those startups, paying salaries and marketing costs, could do so only because of the generosity of altruistic shareholders and lenders. And their altruism was fueled by free money.

If interest rates on term deposits were 6-7%, many, if not most, of the startups funded by venture capital and private equity since the GFC would never have seen the light of day and therefore would never have signed an employment agreement.

And the longer rates remained at zero and QE provided liquidity, businesses that should not have existed not only survived but thrived and grew.

The growth of these businesses was the unprofitable kind. It did not matter whether a profit was made because money was free. The mantra was simple; grow revenue, take market share, and worry about profits later. Unprofitable businesses however are not self-sustaining. They exist purely because generous investors keep cheering them on with their wallets.

Creative destruction destroyed incumbents

But there’s a downside and a terrible social cost. Incumbent businesses – often profitable but old-worldly – went bust as the bright shiny new idea took customers at a zero or negative margin. Nobody made money. The free money-wheeling investors tossed their dollars at shimmering new startups to see just how much creative destruction they could muster. And if at the end of the exercise, when all the competition was dead, the business did turn a profit, well that was a bonus.

But it wasn’t the plan.

The plan instead was to sell the fast-growing company to unsuspecting mums and dads through an IPO. Let them worry about how to turn a profit. And if the company didn’t, it’s the mums and dads who bought into the IPO that would lose, along with the employees and the incumbents.

The venture capital investors simply needed the business to grow large enough to reach IPO. Unshackled by the need to make a profit as a going concern, these businesses could adopt stupid and unprofitable pricing models and operate with impunity by blinding regulators and city officials with the promise of making the world a better place.

Back in September 2019, in an article entitled How soon until we see the collapse of profitless prosperity?, I asked:

“Is it just me? Or have investors in loss-making US technology companies, like Uber, gone completely insane?”

I then referred to WeWork’s 2018 US$1.7 billion loss and Uber’s US$3 billion operating loss in the same year:

“In normal circumstances, if a company announced that kind of loss, with no immediate prospect of stemming it, its shares would plummet. But today, the two companies still have an estimated market capitalisation of US$80 billion to US$90 billion. That’s roughly the same market capitalisation as the Commonwealth Bank which generated US$6.7 billion in profits in 2018 or Volkswagen (US$14 billion in profits), Morgan Stanley (US$8.5 billion), Christian Dior (US$3 billion), Lockheed Martin ($US5 billion) or Caterpillar (US$6.1 billion).”

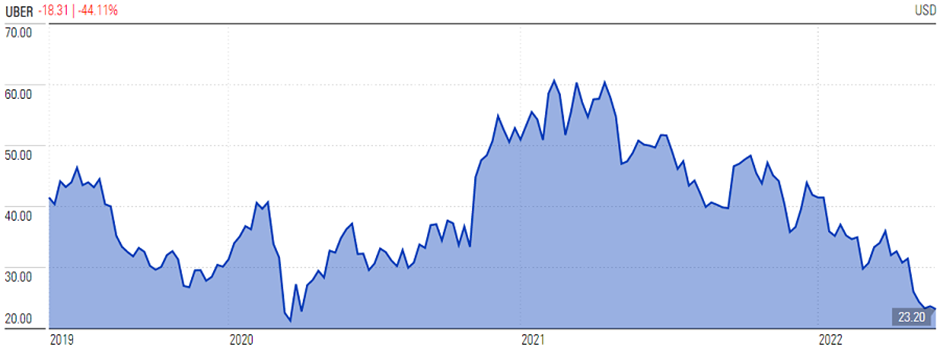

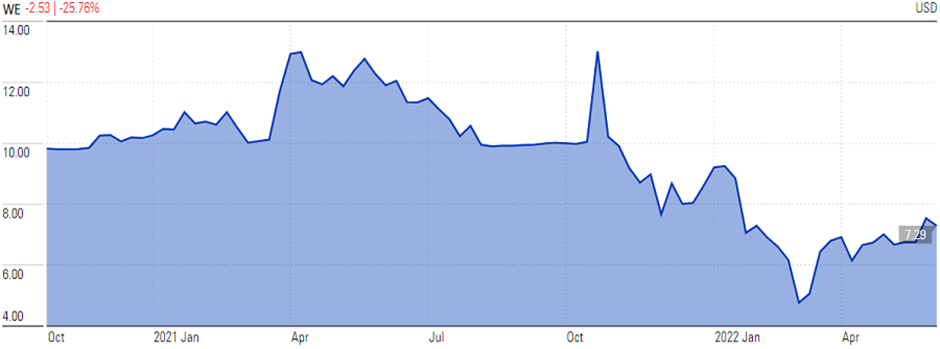

Today, Uber’s market capitalisation, after a 62% share price fall from its high, sits at US$45 billion. WeWork’s market cap is just US$5 billion.

Source: Morningstar.com, as at 2 June 2022.

Multiply WeWork and Uber’s travails across the spectrum of profitless, artificially-propped-up hopefuls, and the destruction of wealth, the opportunity cost, and the missed productivity improvements to nations is immense.

Shareholders taken for a ride

In July 2019, I reviewed the 25 US tech companies that had IPO’d that year, raising a collective US$19 billion. The average gain on listing was 34%, although less than half could be classed as major tech companies. They were (percent gain from IPO to 3 July 2019): Beyond Meat, (>500%), Zoom Video (+170%), PagerDuty (+120%), CrowdStrike (+110%), Pinterest (+45%), Chewy (+47%), Fiverr (+30%), Fastly (+10%) and Lyft (negative).

The consequent share price falls from all-time highs of those same tech superstars is blood curdling: Beyond Meat is down 89% from its high, while Zoom Video is 81% lower. PagerDuty is down 57%, CrowdStrike (-44%), Pinterest (-77%), Chewy (+79%), Fiverr (-87%), Fastly (-87%) and Lyft is 77% down from its high. All have cratered.

In the absence of profit, and without continuous funding supplied by generous shareholders or junk bond investors many of the market’s former darlings will go broke. Thousands of jobs will be lost and damage to the economy will be significant.

Already the funding of these companies is drying up. In May, junk bond issuance of US$2.2 billion was a fraction of the near US$50 billion in the same month a year ago. May’s issuance was the slowest in 20 years. And according to Bloomberg, raising cash in the leveraged loan market has been equally depressed with new loan starts of under US$6 billion in May compare with more than US$80 billion in January.

Initially a round of mergers and takeovers will mask the suffering being felt by many profitless companies and their employees but the more expensive money becomes, the more likely a trickle will become a raging torrent of bankruptcies. And when that happens, a ‘soft landing’ becomes less likely.

We always knew the era of free money would have bad consequences. They have arrived.

First published on the Firstlinks Newsletter. A free subscription for nabtrade clients is available here.

Roger Montgomery is Chairman and Chief Investment Officer at Montgomery Investment Management. Analysis as at 8 June 2022. This information has been provided by Firstlinks, a publication of Morningstar Australasia (ABN: 95 090 665 544, AFSL 240892), for WealthHub Securities Ltd ABN 83 089 718 249 AFSL No. 230704 (WealthHub Securities, we), a Market Participant under the ASIC Market Integrity Rules and a wholly owned subsidiary of National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937 AFSL 230686 (NAB). Whilst all reasonable care has been taken by WealthHub Securities in reviewing this material, this content does not represent the view or opinions of WealthHub Securities. Any statements as to past performance do not represent future performance. Any advice contained in the Information has been prepared by WealthHub Securities without taking into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on any such advice, we recommend that you consider whether it is appropriate for your circumstances.